For how long the compulsive compsumption of images and compressed reflections will remain an acceptable way to approach architecture? The range of readers who demand the pleasure of enjoying a good publication in their hands is surprisingly growing. As the abuse of commercial and acritical content is being detrimentral to architecture itself, the labor of publishing houses committed with knowledge management and quality is becoming increasingly appreciated.

Aware of how decisive is the way of communicating architecture in its cultural construction and social value, Andreas and Ilka Ruby (an architectural historian and architect respectively) have spent five years exploring new routes from Ruby Press. The Ruby opt for the printed book as a vehicle for critical perspective, creative exposure and literary and artistic quality. Their work is crafted and selective. They analyze projects and topics of interest in depth, do facilitate understanding of the content and pleasure in receiving it. Their ambition is to create publications able to start conversations and generate new ideas in the readers. In this interview we had the pleasure to enter into a publishing project that arises from the passion to communicate the architecture to be shared, understood and valued.

PAULA V. ÁLVAREZ: It’s a well-known phenomenon that digital culture has radically changed reading habits. We have got used to fast reading and fragmented attention, to receiving information simultaneously from different devices, to jumping from one information to another. Readers construct their stories out of digital online “storage” in the forms of exquisite corps, able to have its own life beyond authors and publishers’ intention. From your experience as readers, writers and editors, what challenges are posed to the printed book by these new ways of reading? Do you think that books have to accept and incorporate these changes or they must attempt to overcome them, maybe even counter them or open new perspectives? How do you see the current situation of the books and their real use by society?

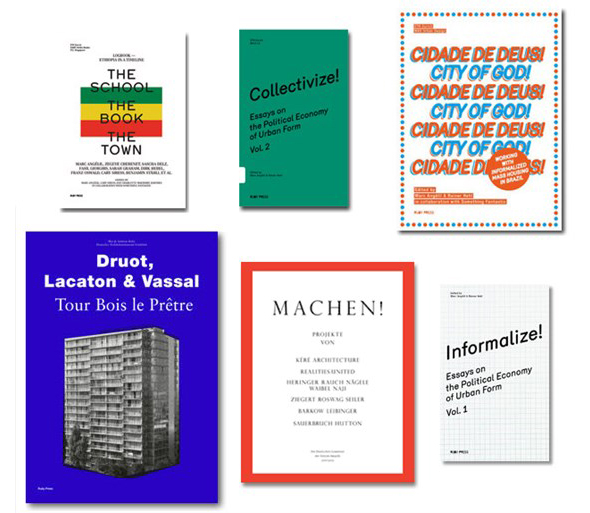

ANDREAS RUBY: The digital culture makes printed books not less, but more relevant. There is a new division of labour. Digital channels are used for fast and short-term information, you read and forget quickly. But its hard to find quality information. If you are searching for material about an architectural project, for instance, you will quickly find some photographs on many different sites (yet mostly they always the same). But its much harder to find good drawings. For that you basically still need to refer to books, which brings us to the physical nature of information. On the screen, things have no scale. You just zoom in and out endlessly. But books, like buildings, have a definitive scale, and it makes a big difference if I tell a story in a small pocket size such as our theory series Essays on the Political Economy of Urban Form or in a monumental A3 portrait format such as our Catalogue on the Tour Bois le Prêtre in Paris by Druot, Lacaton & Vassal. While the sensual impact of a webpage is always conditioned (and to some extent neutralized) by the standardized format and default materiality of the monitor’s backlit projection, a book presents its content to the reader always based on its specific format, paper, texture —the look and feel of a tangible object. You can’t touch the information on a screen, and if you do you will make greasy spots on your glossy display which will further distance the content you try to access.

There is an innocent joy in the “there-ness” of content embodied in a book. It’s that particular print colour over which I can rub my thumb, it’s that kind of smell that attracts or repels me (it will never leave me sensually indifferent), that magic satinated surface of the paper which partly soaks the printing ink inside, partly lets it sit on top. I like the games books can play, seducing and manipulating the reader in lustful ways. Peter Markli’s monograph at AA Publications (edited by Mohsen Mostavafi and designed by Frost) does that nicely: it’s a very big, almost square format and a couple centimeters thick. You expect it to be heavy as you grab for it. But when you finally hold in your hand, you are surprised how light it is. This impression was of course carefully planned by the designers. They chose a kind of printing paper which has a high volume, but low density, and therefore a comparatively low weight. In this way the choice of paper undermines the monumentality of the format, and what could easily have come across as a heavy-duty gravestone-like monograph performs now a very subtle critique of the narcissism of architectural representation. For such maneuvers you need the extremely rich and historically developed phenomenological palette of traditional book making. I have the feeling that the more we go digital as a society, there is a growing community of book lovers who care for this sensual specificity of content in books. Hence I think the printed book has its relevance and legitimity in the digital age as well.

P. A.: In recent years there have emerged, like islands in a sea of undifferentiated and uncritical information, numerous magazines in paper format: Criticat, Le Journale Spéciale’Z, San Rocco or Monu. Having different approaches and interests, these publications seem to share a common agenda: to stimulate a debate about architecture in relation to the economic, environmental and sociocultural context in which it occurs. Would you say this expansion is an indicator of an interest in criticism? Where does remain the edition of books in this scenario of critical reflection? I mean, can the book format provide a vehicle for criticism or critical culture? What would be its strengths and influence as such?

A. R.: Magazines and books serve different purposes. A magazine can stir a debate by bringing one particular topic or approach to the fore. A magazine teases the Zeitgeist and provokes its community to react and produce more content. Books on the other hand tell stories. They can and should explore a subject much deeper than a magazine ever could. A book basically unfolds a narrative and asks the reader to follow it on this path, it is a journey you make together, and that’s a very different state of mind compared to the reading attitude in the case of a magazine. Nonetheless, a book can be a vehicle for criticism just as much as a magazine, if it is able, through and beyond its narrative content, to frame a new way of looking at the world. Architects without Architecture or Learning from Las Vegas were such books for me: They made me see the world of building in a new way and defined new criteria of judgement which came in handy to value examples of the architectural production at large.

I also like a book like The Charlottesville Tapes very much, which attempted to criticize a certain kind of discourse of architecture that, according to the protagonists of that book —the who’s who of architectural postmodernism from Eisenman to Krier to Ando—, was too much dependent on the discourse of critics while excluding the voices of architects as discursive protagonists, not just makers of buildings. This book has transformed the way in which architecture was discussed in the 1980s probably more than any magazine of that period, because it gave examples of how you can make an argument for or against an architecture that was free of the self-indulgency of the know-it-all critic who first and foremost needs to establish the superiority of his/her (mostly his, though) judgement.

P. A.: Personally I would place Ruby Press as part of a recent exploration of ways of conceiving publications that dissolve the difference between magazines and books, printed and digital communication. An example is the exploration of non-linear narratives in Something Fantastic, A Manifesto (2010) or the overlapping of layers of information and the multiplication of entrances in Urban Transformation (2008). Are you interested in developing forms of interactivity that take advantage of the intrinsic possibilities of the printed format? And what about ways of combining information technologies and printed matter?

A. R.: Principally I am interested in books that operate on multiple layers. For that reason we try to avoid pure text books or pure image books. We like to combine text and images in interlocking layers. Some things you can better communicate with text, others better with images. I like books which allow for different ways of reading; for instance that it contains parts where you really can and have to enter deeply in the subject matter, but as well parts that you can more or less flip through in a more lighthearted manner. Hence you can enjoy different rhythms and speeds in a book. Roland Barthes, one of my favourite writers, wrote in Le Plaisir du Texte that probably no one ever read the books of Proust or Balzac word for word from front to cover with the same attentiveness. Sometimes you ruthlessly thumb over entire pages of meticulous description of sofa decoration and embroidery details because you are simply dying to know whether the niece falls in love with the gardener or not (the lucky thing with Proust, according to Barthes, is that with every single reading you jumb different passages, never the same). For him, the pleasure of the text emerges when the reader takes his or her liberty to speed up or slow down the flow of the text. We try to embody these different speeds and densities of information already in the way we compose our books.

I also like books that manage to cater to multiple audiences with different interests. Alfred Hitchcock was a master in this art. He always made his movies in such way that at least two very different kind of audiences could enjoy them to the fullest. Basically, they absolutely work as classic crime thriller or detective movies driven by the lust for suspense (the whodunit genre). But you can just as well look at his movies with a primary interest in psychology, indulging in issues such as fear, guilt, inhibition, as Slavoj Zizek did in his study Whatever you always wanted to know about Hitchcock but never dared to ask Lacan. To generate that kind of openness in which readers can use a book is my biggest motivation in my work as an editor and publisher.

P. A.: I find very interesting the parallelism that you do between the editors’ work and other creative jobs related to post-production, such as a movie director or a music producer. Post-production processes are nowadays so sophisticated that they let us think of editing as a work of author itself, a kind of authorship based on multiple micro-decisions and manipulations of the work of other authors as raw material. How do you deal with this type of creative mediation in your books?

A. R.: Yes, I see the music producer as a kind of role model for the work of an editor and publisher. As someone working behind the scenes as a musician, an engineer and an entrepreneur, the music producer has an often underestimated creative influence on the final musical outcome, as he is involved in the entire process of making a track, from song selection and composition through mixing and mastering. Good producers create really the sound of music, such as George Martin created the sound of the Beatles or Quincy Jones made the sound of Michael Jackson. A producer defines the conditions of perception of a piece of music, he defines the filters through which the music will reach your ear. An editor/publisher for me does the same with books. You take a piece of content and ask yourself how you want it to sink into the consciousness of a reader. By doing so, you inevitably place yourselves between all kinds of chairs, you interfere with the work of other protagonists: writers, graphic designers, printers, to name but the most central roles. You experience a kind of distributed authorship, in which the final outcome of the book can rarely be traced back to one single individual. Rather it is like playing football: You have one ball but 11 players to pass it around, and together they will define the course the ball is taking.

When we make our books, we usually work together with our authors and editors from the very first moment. At the beginning we try to understand and sharpen the thesis of the book, by reviewing the content together with them, dismissing some parts and post-producing new ones. We work on the level of writing, in order to find the tone and genre appropriate for the message of the book. We tie in our graphic designers from Something Fantastic (who are also architects) always from the very start of the project. They contemplate the content on their part (which is not the usual case with graphic designers) and make their own interpretation of the content which we can then push together to yet another level. The role we occupy is somewhat akin to how Socrates describes himself in Plato’s famous dialogues. In Theaitetos, he refers to himself as a midwife helping Theaitetos to bring out his own thinking, simply by the asking the right kind of questions. That for me is a fairly interesting concept of a publisher today.

Seville / Berlin, 2013.

To deepen on Ruby Press work and current publishing challenges, we recommend the article “When Editors Become Publishers: Ruby Press” by Nathalie Janson. This article offers an excelent background to understand Ruby Press work and, in addition, it clearly explains many key points about the rather obscure and unknown field of publishing practices and their logic.

More about Ruby Press books here.